When it comes to implementing sustainable water and wastewater management in megacities, water prices are decisive. They are the basic means of raising the revenues needed to maintain, improve and extend water infrastructure. Moreover, prices set the incentive to use the scarce resource water efficiently, i.e. to reduce overall consumption and to allocate water to those uses with the highest economic and social benefits. Getting the prices right is particularly important for Lima where the infrastructure is highly deficient and water is extremely scarce.

Economic theory suggests that water prices should include the full cost of water supply and sanitation (investment costs, operation and maintenance costs, opportunity costs and external environmental costs). However, policy-makers also have to make sure that the poor can afford to cover their minimum water needs and that the implementation of the water price actually survives the political process. To identify the implementation conditions for water prices, a systematic framework is developed within the LiWa project, organising the political, legal, informational, technical and other factors.

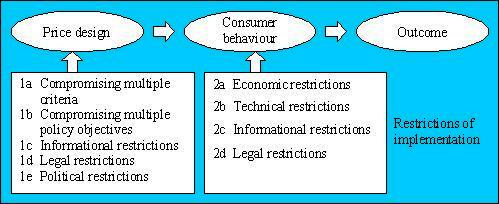

This framework clarifies that the outcome of water pricing depends on 1) the actual design of the water price and 2) the resulting consumer behaviour as a response to the price. In the real world, however, both elements are subject to various restrictions which may eventually affect the outcome of a water price (see Figure below).

A preliminary evaluation of Lima’s water pricing system has been carried out in order to identify the most important challenges and problems.

Taking into account the analytical framework, the following challenges have been identified:

1) The average level of the price is too low in terms of efficiency and cost recovery. It considers operation and maintenance costs but not capital costs, opportunity costs and environmental costs. A low level may be desirable, though, in terms of affordability.

2) Price discrimination under the increasing block tariff implemented in Lima violates efficiency, which would call for uniform pricing per unit of water. Theoretically, price discrimination is a means to address affordability. It may result in adverse effects, however, with joint connections and an insufficient coverage of metering.

3) The assessment base of the water price lacks a differentiation with respect to water consumption, wastewater production and contamination. Consequently, polluters may inefficiently externalise the cost of water pollution to other water users. This effect results in a generally higher price level for all customers and thus reduces the affordability of water supply.

4) There is a general lack of regulation for decentralised water supply. This is inefficient as it results in higher prices for decentralised supply then for grid-based supply. It also impairs affordability as it is usually the poorest which are not connected to the grid.

5) Insufficient monitoring and enforcement of water prices inefficiently distort the actual incentives from pricing and reduce the overall revenues from pricing needed for cost recovery (e.g. due to illegal withdrawals, manipulations of meters, etc.).

6) The lacking perception of water as a scarce and valuable resource produces political opposition against price increases to a level which would be efficient and cost-recovering.

Challenges 2), 3) and 4) were chosen for analysis in further detail – as they were identified in stakeholder discussions as particularly important and urgent issues and promised interesting and new insight from a scientific perspective.

Contact: Paul Lehmann; Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ)